Rezensionen/ Presse

Der Gesamtüberblick findet sich im Menu unter "Biografisches"

Texte von Eva Dotterweich (2011), Bernd Hägermann (2010), Christian Neuhuber (2009), Inka Sommerfeld (2008), Beatriz Szonell (2008)

Testi di Franca Cavagnoli (2010), Carlo Quadrino (2008), Philippe Daverio (2006), Giorgio Cusatelli (2001)

Text by Franca Cavagnoli (2003)

Eva Dottenweich

Franca Cavagnoli

Storie di funamboli, nocchieri e pierrots lunaires

Bernd Hägermann

Christian Neuhuber

LENZ-BILDER

Bildlichkeit in Büchners Erzählung

und ihre Rezeption in der

bildenden Kunst

Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar, 2009

S. 314ff

Carlo Quadrino

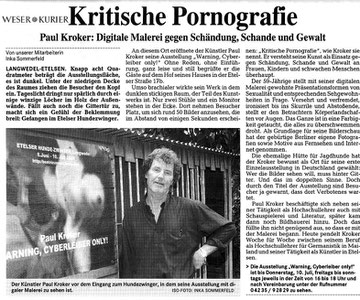

Inka Sommerfeld

Beatriz Szonell

Warning, Schule des Sehens!

Philippe Daverio

Paul Kroker, berlinese, dovrebbe tendenzialmente vedere il corpo nella versione autopunitiva germanica: pensate alle pustole incredibili del diavoletto che se ne sta seduto nelle Tentazioni di Sant’Antonio di Matthias Grünewald. Nessun italiano avrebbe sopportato la vista di quelle pustole. Sono i mostri di Max Ernst, che tirano via la barba al frate, poi c’è un altro animaletto surrealista, e infine sotto c’è una sorta di umanoide con un corpo abietto coperto di pustole. Ritroviamo elementi analoghi e straordinari, non necessariamente germanici, nel museo di Varsavia.

Tutti i popoli del nord, tutti i derivati della grande migrazione, hanno una visione del corpo non del tutto risolta. È questa la visione normale del corpo che dovrebbe avere Paul Kroker. Lui, invece, ha compiuto un gesto osceno: è uscito dalla sua scena e ha deciso di vivere a Milano. Ha fatto un salto in una cultura diversa, e nel fare questo salto in una cultura diversa ha scoperto il gesto osceno suo, cioè quello del corpo che invece di essere ciò che doveva sembrare – pustoloso - diventa il corpo che colloquia con l’oceano.

Il corpo, cioè, che viene costantemente massaggiato dall’idea del bello, da un’idea estetica del bello, che è il corpo dell’etrusco. Le sue signore, di cui vediamo qui soltanto tracce di chiappe e di seni ma che sono nascoste dietro delle reti d’oro, sono delle signore che non appartengono più alla sua originaria cultura tribale da nomade, bensì corrispondono a chi è stanziale e da stanziale va a pesca, va in quel mare lì e quel mare lì non fa male. Quel mare lì permette di abbronzarsi. Quindi alla fine lui ha compiuto un gesto osceno con un grande corpo come il mare.

Philippe Daverio, Corpo a corpo con l´osceno,

28.1.2006, Istituto di Cultura germanica, Bologna

Franca Cavagnoli

Angele

A

dismal and desolate landscape, scorched by flames, dotted with bituminous scrub. Few, subdued patches of colour: ochre, pearl grey, purple. The sky has fallen on this barren land, and lies

shattered. Out of its ruins – or before touching the ground, perhaps? – a leaden wing rises. A bird’s wing? An angel’s? Undoubtedly, however, a wing that can no longer fly nor ever could. It lays

heavily on the waste land of straw and string and tin.

The torment of this wing is depicted in Kiefer’s painting Das Wölund-Lied. But the desolation on the canvas is simply the reflection of the inhuman desolation that dwells in the heart of German

artists more than it does in the heart of any other European artist. Fifty years ago Vercors had one of his characters, a Wehrmacht officer, say about another artist and fellow countryman: “Bach…

he could only be German. That is the character of our land: an inhuman character. I mean, not pertaining to a human being.” Thus is the most prominent feature of Paul Kroker’s Angels: they are

creatures that are no longer angelic nor yet human, they are inhuman in the sense that Vercors gives to the word.

Their journey was not from earth to the sky: they are fallen angels, or maybe they simply descended, drawn by the mystery of humankind. But mysteriousness draws and allures, and sometimes its

very charm is what hinders knowledge. Not here. Indeed, these creatures appear to have descended to earth to penetrate the essence of human suffering, as they remain suspended on the very thin

rope that divides the corporeal from the spiritual. After all, how could an artist from Berlin not measure himself with the thin line of separation, being as he is more used than anyone

else in Europe to measuring himself with the firing line that split his city, his country and our entire continent in two for decades? His creatures are therefore destined to remain in exile forever,

just as the artist who conceived them is displaced: their gaze half-turned back, like an emigrant’s, scanning the dust in search for the now unrecognisable traces of the homeland they have lost

or left.

Paul Kroker has often stated that, “Those who know me know that my work has always been centred on the figure of woman, her suffering and joy as well as her passion and passionateness. Then, years ago, a revengeful streak set in as well. By revengeful I mean self-destructive, obliterating.” In these figures the suffering of woman – her passion – seems to have clotted into the bloody material we can perceive inside them, for not a single drop of liquid seems to have come out of their knife-, scissors-, grenade-inflicted gashes; their blood seems to have spilled inside, where the world’s pain they bear condenses. Some still preserve the heritage of the heavenly homeland they lost or left – their wings – while others are now wingless but have yet to grow limbs. Once again, they proceed with the sole force of their passion-ruling vital organs along the intangible yet distinct line between being half and half. They are constantly seized by an unmentionable suffering that leaves them injured, mutilated, racked with pain in a body that is no longer spiritual and not yet human. Even though the wings are made with very light material – Kroker uses humble materials: plastic, cardboard, papier-mâché, rags – and hence by no means comparable to the tin or lead that hinder the movement of the wing fallen from the sky in Kiefer’s painting, still we know that these Angels will never fly off again either.

Golden figures and white figures. Gold, the emblem of a sacredness ever violated and transgressed by the actions of the subject it clothes. Golden angels heavy with thoughts, the highest expression of an excessive cerebralism that leaves room for nothing else, of pure thought, of cold and detached abstraction. Could this be why Kroker’s statues are all decapitated? Is their head, rather than their passion-ruling organs, the driving force behind their pain then? The prong does indeed comes out of the belly, like the tentacle of an octopus that might be closing its grip on the humour-producing organs, closely threatening bile ducts, enlarging livers, causing bile to gush, drying up pancreases and spleens and stripping them of their primary functions. These figures seemingly want to remind us that having no head does not mean having no thoughts: if the head is too saturated with thoughts that do nothing but spin around, if thought turns into excessive cerebralism, grows exasperated and does nothing but vex the mind, then there is only way out, one leading towards lucid madness.

Beside the gold is whiteness, the symbol of a mourning that nothing will put an end to. What is the mourning these crumpled-winged women will never manage to work through? What story might they tell – deprived as they are of a mouth to voice their thoughts with, of eyes to frown at us, or to be crossed by a veil of melancholy or by a flash of sudden irritation – if we were to draw near and listen to the motion of their soul? Perhaps they would tell us about an apocalyptic age where their life could only accomplish its own slow self-dissolution, just like another German, a son of last century’s closing, managed to tell with blazing intensity in his books. Like Sebald’s Austerlitzteaches us, being able to remember can be a curse, although nobody manages to keep away from the arsenic that contaminates the headwaters of memory. Still, there must be a journey going on in this ethereal white body towards the sources, towards the deepest and darkest regions the light that illuminates our inner space bursts forth from, the only antidote to arsenic that humankind has ever managed to discover.

Figures that receive death and give themselves death but give it in turn as well. What might indeed befall the unwary person who dares go near that prong coming out of the belly? Or that rope cutely worn around the neck like a necklace or a scarf. What purpose can it serve, other than to hang oneself? Thus they are never solar angels, despite the gold’s brilliance, but nocturnal angels, wet by the moon’s silver. Angels of passion. These statues used to have chains of small dancing figures on them that I never found joyous, let alone playful, given how mangled their bodies were. What we see now appears to me as the artist’s natural evolution towards genuine disbelief, the impossibility to believe in life as such, only in the salvific strength of his own power to imagine it. And the earth these she-angels have descended to does not look blinded by the flash of the sublime or of the sacred, but crusted over with the miasmata of a now withered soil. They are figures destined to roam among us, along the thin line of their inhumanity, on a waste land from which it seems no more lilies will ever spring again.

January 2003

(Translated by Andrew Tanzi)

Giorgio Cusatelli †

Vorrei riprendere l’idea di un convegno su Novalis da una di quelle sculture che Paul Kroker ha esposto ed espone tuttora presso la sede del Goethe-Institut. Si tratta di oggetti d’oro che non sono tanto oggetti, non sono Gegenstände si direbbe in tedesco, ma propriamente sono Dinge, cioè entità, res. Questi oggetti d’oro sono avvolti con un sottile filo azzurro. È quasi simbolica una figura del genere perché l’oro è il pensiero e la sostanza della presenza di Novalis nel mondo e il filo azzurro è naturalmente die blaue Blume, è la presenza contingente del reale nel quotidiano dell’opera di Novalis. detto questo in affettuosa dialettica con Paul Kroker, non tanto penso all’attualità di Novalis quanto alla perennità di Novalis.

dal saluto al simposio Utopie romantiche,

Università degli Studi di Milano,

23 marzo 2001